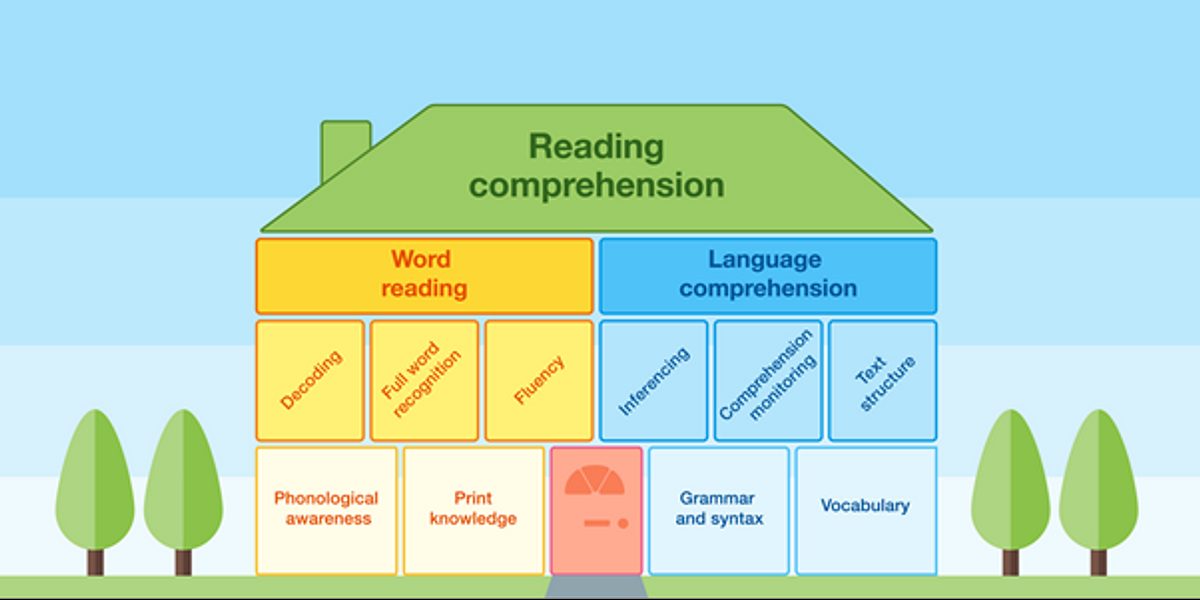

Let’s return to the reading house, this time, thinking about the ‘cement’ – that may hold the house together – background knowledge.

A snapshot from my classroom

My Year 5 class have now finished Chapter 1 of The Nowhere Emporium by Ross MacKenzie. We’re questioning and making inferences about the world of the central character Daniel – narrowing in on specific details from the story:

‘The shop was a cave of wonders… Intricate wooden clocks and mirrors of varying size and splendour covered the walls…There were porcelain dolls and wooden soldiers; rusted swords; stuffed animals; columns of books as high as the ceiling; jewels that seemed to glow with a silvery light.’

My first question: ‘what is your first impression of the emporium?’

In order to respond to this question, my students will need to make successful coherence inferences: they will have to construct their understanding of the text based on the grammar, syntax and vocabulary.

That’s often hard enough. However, elaborative inferences are the real sticking point. These require pupils to lean on their background knowledge and broader life experience in order to fill in the blanks where a text omits key details.

- Although some of my pupils have had opportunities at home to build their general knowledge, there are still plenty of others in my class who have not accessed opportunities to develop their knowledge and experiences of the world.

Those pupils who have read Arabian Nights are more likely to understand the connotations of ‘a cave of wonders’.

If they’ve visited an aquarium or kept a pet, when they hear ‘tank’ they won’t be as confused as their classmate, who first calls to mind the army vehicles they’ve seen in video games.

The pupil who has visited antique shops can imagine this jumbled emporium selling porcelain dolls, stuffed animals and rusted weapons. How bizarre it can be to try and imagine these objects on a supermarket shelf – the type of shop mostly visited by my pupils!

Those pupils in my class who haven’t had these experiences of the world – well, they are left struggling even to read and understand words here that they’ve never encountered before. They are not always able to form basic comprehension of what they are reading, never mind form deeper elaborative inferences.

The background knowledge our pupils activate when reading emerges in that deft interplay of questioning where inference-making happens. It can prove the cement that holds together the blocks of the reading house.

How then do we teach background knowledge so that pupils can make successful inferences about the text as they read?

Explicit Vocabulary Instruction

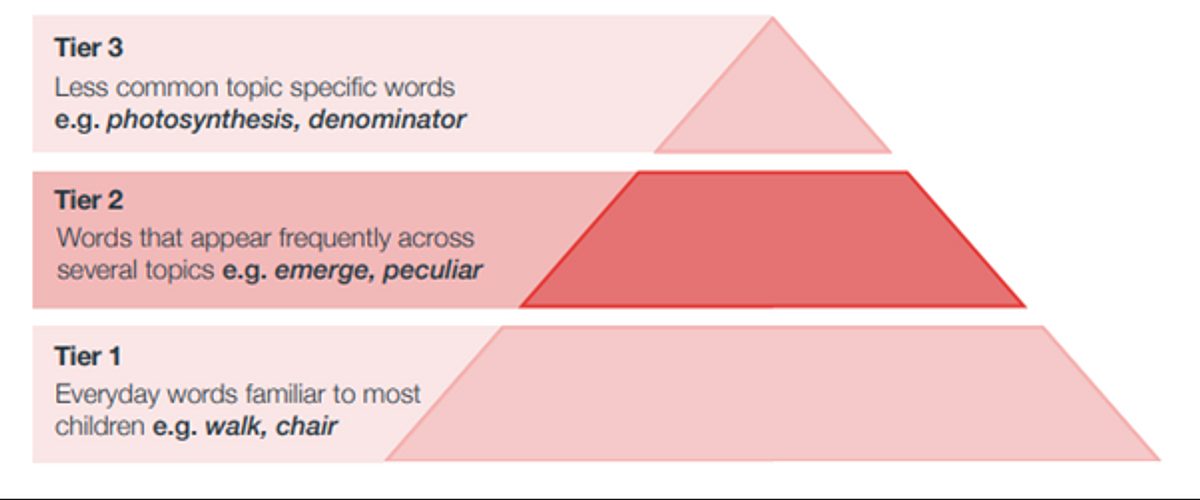

The EEF’s Key Stage 2 literacy guidance report suggests that a useful starting point is to consider Beck and McKeown’s tiered vocabulary approach:

As detailed in the report, focusing on teaching Tier 2 vocabulary could be helpful in boosting the background knowledge that fuels elaborative inferences. These are the words that ‘are not the most basic or common ways of expressing ideas but are familiar to mature language users as ordinary as opposed to specialized language’.

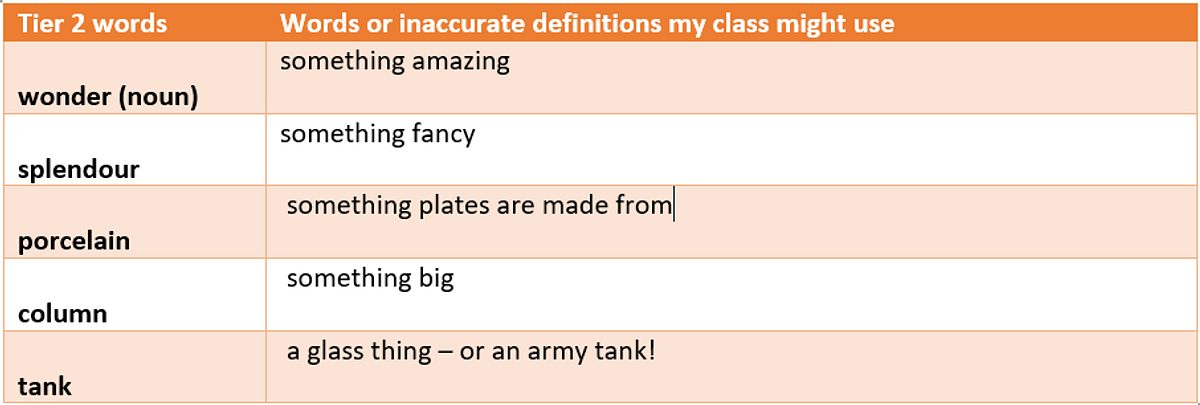

Tier 2 words from ‘The Nowhere Emporium’ extract could include:

Armed with the words and concepts I need to consider to ensure successful inferencing, I now consider more precise definitions and some practice steps for my teaching.

Beck and McKeown offer a range of robust instructional activities which could support my pupils in building knowledge and understanding:

1. Compare examples and non-examples to establish meaning.

Splendour means:

a) Something with a very grand and impressive appearance

b) Something pretty

2. Pair two unrelated target words, to support students encountering words in novel contexts.

Can splendour ever be unpleasant to look at? What would a castle made of porcelain be like?

3. Present two or three slightly altered definitions of a target word over a series of lessons, to deepen thinking and understanding.

Wonder (noun):

Something that people admire: the pyramids are a wonder to look at.

Being excited by something awesome or mysterious: the boy looked in wonder at the chest of rich treasure.

A miracle: it is a wonder you weren’t bitten after stroking that crocodile!

Using such strategies to teach vocabulary alongside inferencing practice in my sequence of Year 5 lessons can unlock the background knowledge my pupils need for those pesky elaborative inferences. My planning potentially moves beyond accumulating word lists and definitions to building rich, imaginative understanding.